Driving through many of Syracuse’s neighborhoods today, one can’t help but notice the boarded up vacant houses, trash-strewn vacant lots, crumbling porches, and chipping paint. One might ask, how did this happen? How did we get here? What impact does neighborhood blight have on the city and its residents? What are the consequences to living in unstable and unsafe housing? And how does it affect our residents’ access to opportunity?

Historical Housing Policy and Concentrated Poverty

One explanation is simply that the housing stock in Syracuse is old, with 44% of homes built in 1939 or earlier. In addition, post WWI and depression era housing was built quickly and cheaply to accommodate manufacturing families. This housing is particularly found in our North-, Southwest-, and South-side neighborhoods that suffer from high rates of poverty, with up to 64% of housing in those census tracts being built in that era. But the explanation is not that simple.

From around 1910-1970, the Great Migration brought Blacks north to Syracuse and other industrial cities searching for economic opportunity. But federal and local housing policies in the first half of the 20th century pushed families of color into neighborhoods with less desirable housing stock. These same neighborhoods were later “redlined” by the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) from 1934 into the late 1960s. Legally sanctioned, redlining labeled neighborhoods and people that the government (and subsequently the private mortgage industry) wouldn’t provide affordable home mortgages to, effectively denying residents in (or near) redlined neighborhoods the opportunity to build wealth through homeownership. Urban Renewal development projects between the 1950’s and 1970’s further eroded neighborhoods as highway construction in Syracuse decimated the 15th ward, forcibly relocating around 3,500 residents, most of whom were poor and Black. Syracuse used its federal urban renewal grants established under the Housing Acts of 1949 and 1954 to clear blighted areas to form rights-of-way for new highways and modern buildings (like the Everson Museum). And to complicate matters further, government authorities concentrated public housing construction in the 1950s within neighborhoods already struggling. These historical housing policies and practices effectively concentrated the negative effects of poverty in Syracuse.

Map of FHA redlining in Syracuse, NY

Syracuse’s population also started to plummet after having reached a peak of 220,000 residents in 1950. From 1950 until today, Syracuse has lost nearly 75,000 residents. White flight to the suburbs spurred most population loss (while Syracuse lost population, the population of Onondaga County towns and villages steadily rose). Factories followed whites to the suburbs, beginning the first waves of large-scale housing vacancy and abandonment in the city, and leaving those who could not afford to follow jobs to the suburbs in Syracuse’s declining neighborhoods. This extreme erosion of the tax base and deindustrialization (as a result of globalization and automation) gave rise to the service economy and low-wage jobs in cities. Syracuse, like so many other cities, has never fully recovered.

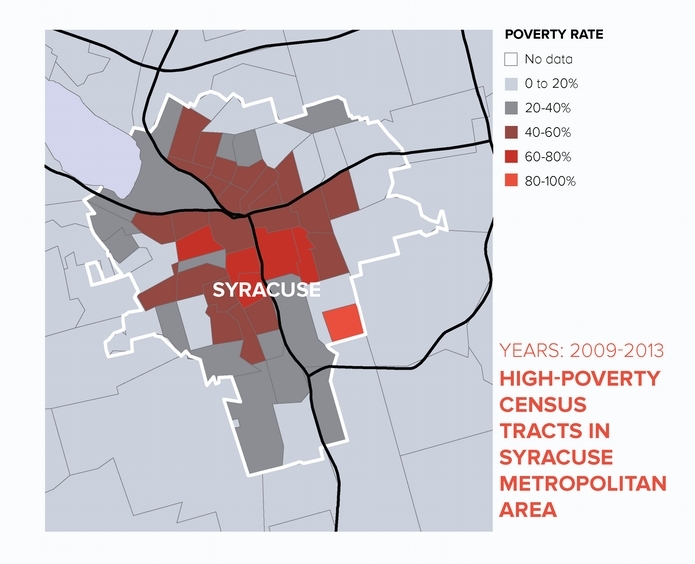

Syracuse's neighborhoods with the highest concentrations of poverty map onto areas that were redlined by the FHA.

Source: Architecture of Segregation, Paul Jargowski, The Century Foundation

The Impact of Poor Housing on Individuals and Families

It has been widely studied that if people have a stable and safe place to come home to, they can more effectively deal with the other barriers and challenges in their lives. Housing quality and stability have real impacts on occupants mental, physical, and financial health.

Financial Burden & Instability

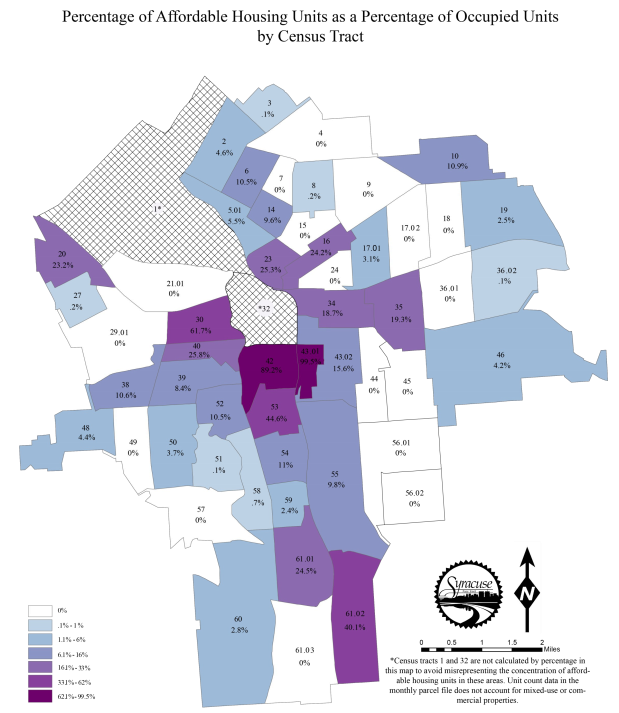

Today, more than 52% of Syracuse’s housing units are renter occupied. Approximately 58% of the city’s renters (and 44% of homeowners) have a housing cost burden, meaning they spend more than 30% of their household income on housing (US Census Bureau). According to the Syracuse Department of Neighborhood and Business Development’s new affordable housing study, only 10.3% of housing units in Syracuse are subsidized to be affordable, leaving a huge gap in access to affordable housing and placing renters in cost-burdened, unstable housing situations. Families facing severe rent burdens are left with little room for other necessities like food or clothing. Additionally, they face eviction when financial crises interfere with rent payment.

Research shows that eviction can have enduring effects on families’ ability to obtain basic necessities (e.g., food, clothing, and medicine), can cause depression, and that housing instability can lead to frequent school moves, high rates of absenteeism, and low test scores among children. High rates of formal eviction - often caused by an inability to pay rent - lead to chronic housing instability and transience for many of our residents. Locally, the Volunteer Lawyers Project (VLP) estimates there are between 8,000 and 9,000 evictions per year in Syracuse. According to VLP, the most significant cause of eviction is failure to pay rent. The SCSD recently pointed to eviction and housing insecurity as major contributors to chronic absenteeism, which contributes to lower achievement in school and a higher likelihood to drop out before graduation.

Source: A Study of Affordable Housing by the City of Syracuse, Department of Neighborhood and Business Development,

Eviction cases represented by the Volunteer Lawyers Project cluster around our areas of the highest rates of concentrated poverty for Blacks and Hispanics.

Housing Quality & Health and Safety

In our research, we found further instability is caused by code violations that make a property unfit to live in, such as having no heat, water, or electricity, or the property having structural issues. When a property is declared “unfit,” it is unsafe to live in and tenants must move if the violations are not fixed within the next few days. While it’s better for residents to not live in these conditions, there is little assistance available to help with a stressful, expensive, and unexpected move. The City’s Division of Code Enforcement cites anywhere between 15 and 44 of these violations a month. People moving from poor or unsafe housing conditions (as a result of code violations or eviction) often end up in worse quality housing, or even end up homeless.

Source: Syracuse.com

Source: Syracuse.com

In addition to causing transience and instability, many housing code violations prevalent in Syracuse directly impact the physical health of residents. A recent CityLab article points out that “broken windows or leaks, insect and rodent infestation, lead paint and pipes, defective appliances, and poor ventilation translate to direct health harms such as elevated blood lead, respiratory ailments, and exposure to cancer-causing toxins.” As of the end of May 2017, 3,644 of Syracuse properties had open code violations. Additionally, almost 91% of the city’s housing stock was built prior to 1979, leaving a majority of properties at risk of containing lead paint since the use of lead was not made illegal until 1978. As a result of this, between 2009 and 2015, 12.3% of Syracuse residents had high blood lead levels, and 2.9% had very high blood lead levels (Onondaga County Health Department). Luckily, according to the Onondaga County Health Department, these rates are steadily declining. Elevated blood lead levels result in reduced health and educational outcomes for children and families and can have lasting consequences.

The Impact of Poor Housing on Neighborhood Health

Housing in poor condition also has aggregate impact beyond the individual household level. The same CityLab article mentioned above also points out that “Housing’s role in public health is about more than lead contamination, pests, or broken windows; it’s also about whether the neighborhood itself encourages exercise, eases the stress of daily living, and deters crime.” Dilapidated housing, abandoned buildings, and vacant lots impact not only those living in and directly next to these structures, but the neighborhood as a whole:

A 2015 study [by] the Ohio Education Research Center at Case Western Reserve University [examined] how housing influenced kindergarten readiness in the Cleveland Metropolitan School District [and] found that children who grew up within 500 feet of a distressed property had lower literacy scores…

Abandoned houses that become havens for crime have a host of indirect health impacts on neighbors. [According to Joseph Schilling, a senior research associate in the Metropolitan Housing and Communities Policy Center], the harm from crime “radiates” throughout a neighborhood: “If someone lives next door to vacant and abandoned property that is used for criminal activity, that wears on them psychologically—it’s a creator of stress.”*

The City of Syracuse has 2,029 vacant residential structures (creating a 14.9% residential vacancy rate) and 154 vacant commercial structures. As of the end of May 2017, 375 properties had trash and litter code violations, and 949 properties were in need of more extensive exterior upkeep (paint, stairs, porch, windows). These high vacancy rates and rates of open code violations are often concentrated in the same areas that were historically redlined and have high rates of concentrated poverty now.

Census tracts with the highest rate of vacancy are the same areas with high rates of concentrated poverty among Blacks and Hispanics.

Census tracts with the highest rate of residential code violations are the same areas with high rates of concentrated poverty among Blacks and Hispanics.

Neighborhood blight has adverse health impacts; it impacts people’s attitude about their neighborhood; it brings down property values; it discourages business investment; and it provides opportunity for crime. The Syracuse City Police Department uses problem-oriented policing in eight designated areas that consistently experience high crime rates. All of these areas coincide with high rates of blighted and vacant housing. The City coordinates efforts between departments to resolve some of these issues. Led by the Syracuse Police Department, in those eight areas lawns are mowed, vacant homes are boarded up, and non-working street lights are fixed. These coordinated efforts have consistently shown positive impacts on crime rates in the targeted areas.

***

The lack of quality, safe and affordable housing and concentrated poverty affect the daily health, safety, and opportunity of Syracuse residents. There are no easy solutions. Over the next weeks and months, we’ll be exploring strategies being employed locally and elsewhere that could make sense in Syracuse to start to address these challenges. Some of these are being tackled by community coalitions and organizations, such as access to affordable home loans and affordable housing development. Others fall more directly into our wheelhouse at the City, like community-based code enforcement with a strong focus on health and safety and coordinated neighborhood improvement to address blight. As a community working together we can start to deploy and coordinate these strategies, policies, and programs. In turn, we can start to chip away at one of the major barriers to Syracuse residents’ access to economic opportunity.